How the CapeHorn Self-Steering Was Born

Article published in Blue Water Sailing, Issue 1, 2024

I became hooked on cruising under sail in my early twenties, when boats were wood, sails cotton and running rigging hemp. However, I never enjoyed being stuck at the helm for long periods and wondered if it could be possible to make my boat steer itself. In 1967, I purchased a 24’ fibreglass sloop and the following year, went into action: with the help of a friend who had learnt welding at the School of Fine Arts, I built a gear from scraps of pipes found in the local blacksmith’s shop. It was inspired by the solution Blondie Hasler used in 1960 in the first Single-Handed Trans-Atlantic Race: a paddle at the stern driven by a vertical vane; when it pivots vertically, the water flow makes it tilt sideways, generating the energy to pull the rudder. I made my fist single-handed passage, 150 miles between Gaspé and the Magdalen Islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

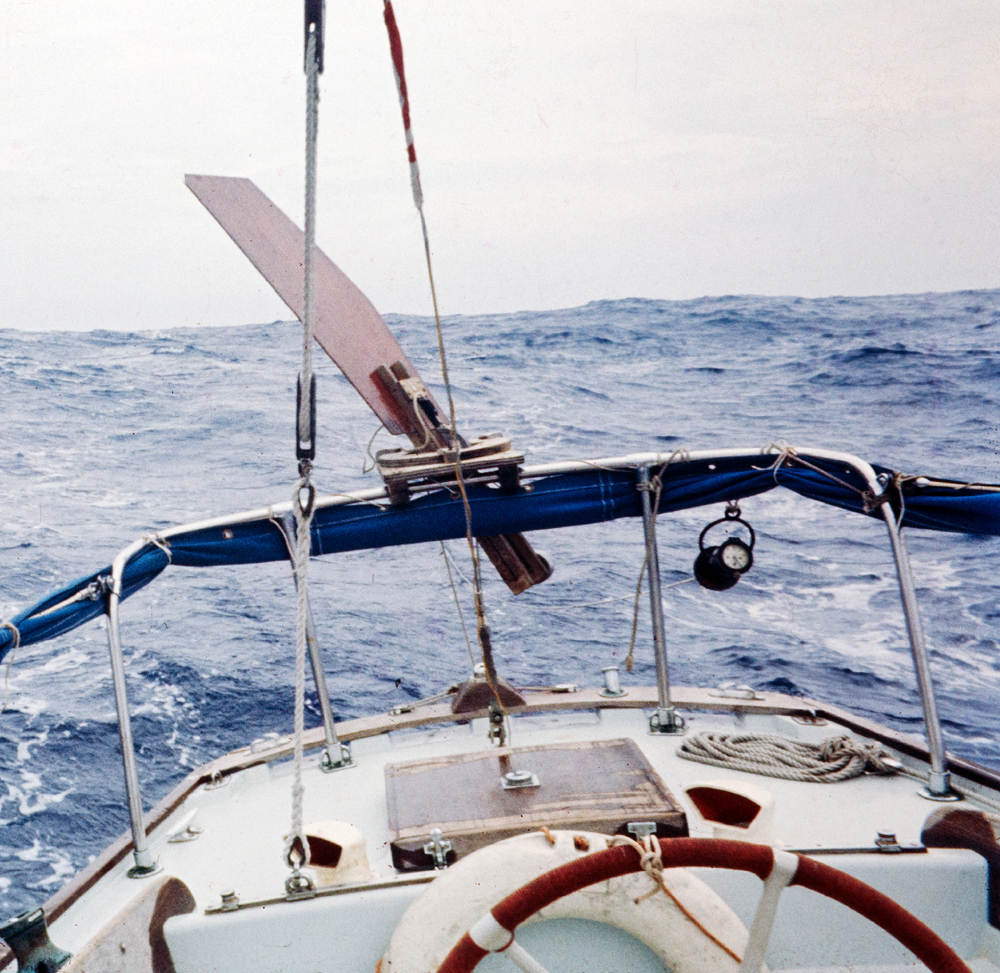

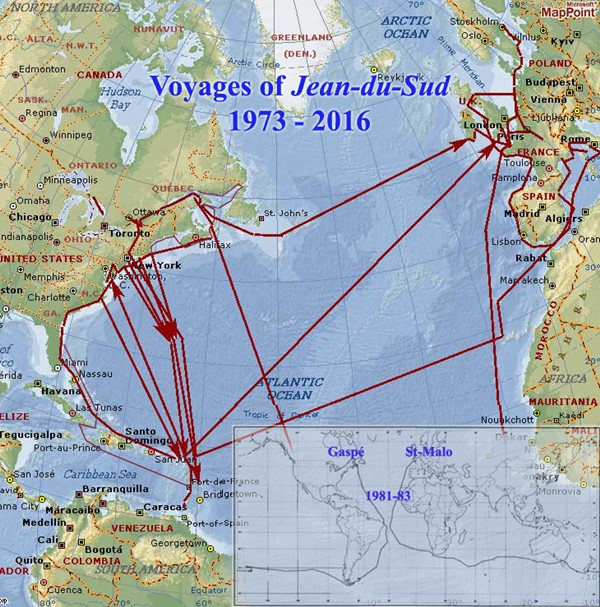

In July 1973 I became skipper of an Alberg 30 I named Jean-du-Sud, after a song by Gilles Vigneault, a poet as important in the French world as Bob Dylan in the English. It was steered with a wheel, so gear #2 was an auxiliary rudder driven by a horizontal vane. It steered me to the West Indies and in the following years, did 3 return trips between there and the East Coast, one trans-Atlantic passage to Brittany, then to Sweden.

Leaving Sweden in the fall of 1978, I was penniless and had no idea where I would land. A letter from a friend, Michel Chabiland, caught up with me in Germany, offering me a job in his boatyard in Brittany. I had met him the previous year and we quickly became fast friends. He ran a yard near St. Malo, on the Rance River where Jean-du-Sud spent the winter. In the spring, he generously placed at my disposal the resources of his yard to refit Jean-du-Sud before I sailed to Sweden. During a stopover in this beautiful anchorage of the Channel Islands, the Isles of Chausey, the last before reaching St. Malo and getting to work, a crazy dream I secretly had for some time suddenly appeared possible: I was offered the facility to prepare Jean-du-Sud for a single-handed voyage through the Southern Ocean, non-stop.

I felt Jean-du-Sud needed something more consistent to put under its keel than simply carrying me as a sailing tourist. After five years I had found the Alberg 30 a good sea boat, built very strongly and had learned to trust it. Yet, with its four ton displacement, it would be the smallest yacht ever to sail that route, once called impossible. With the facilities Michel’s yard offered, I could make my boat strong enough to resist the seas of the Southern Ocean. I knew I could count on his generosity and competence to help me solve the many technical problems I would meet. So beached Jean-du-Sud on sheer legs in Plouër-sur-Rance near St. Malo and learned a new trade. For the first time in my life, I was working with my hands and I remember writing this note: “I have been earning my living for twenty years, but I learned how to work at forty!“

Whoever sailed that route had self-steering problems. Having already built two, I was confident I could design something totally dependable and more elegant than what already existed. Actually, this had never left my mind; I had started experimenting in 1975, during a summer spent on Martha’s Vineyard Island. Over a period of 5 years, I estimate that I have put in the equivalent of one year full-time. If my solution is better, it may not be because I am more gifted, but because I worked at it longer.

I had found the Hasler solution used in #1, that steered through the rudder of the boat, more efficient. Performance was better in light air, especially downwind, a lighter impulse being needed to move a narrow paddle than the auxiliary rudder of #2, that also caused more drag.

But instead of vertical, the servo-pendulum of gear #3 would be driven by the vane invented by French engineer Marcel Gianoli for Eric Tabarly in the 1968 OSTAR: an angle of about fifteen degrees from horizontal provides a greater movement than a vertical vane, yet still proportional to the course deviation.

Gear #3 would be an integral part of the boat, not just an addition bolted to its stern. Regardless of the strength of the wind or the state of the sea, I should not have to worry about its resistance or performance. It would be discreet and would not deface my Alberg 30, a work of art in itself. Throughout the design period, I had this constant preoccupation: simplify; eliminate useless metal. Advantages: less weight, simpler operation and cheaper fabrication.

To install wheel steering, you have to punch a hole through the cockpit sole. To integrate gear #3 to the boat, I did not hesitate to drill a hole through the transom for a horizontal tube. Inside, another tube transmits the tilt of the servo-pendulum at its aft end, to a control arm at its forward end, inside the lazarette. I can’t imagine a simpler or more robust installation. Lines coming from the control arm pull the tiller; if steering is wheel, they are led through blocks bolted to the quadrant in the lazarette, then to jamming cleats in the cockpit for instant connect, disconnect or trim.

But I kept stumbling on this problem: how to transform the vertical movement of a connecting rod coming from the vane, to the rotary movement of a paddle that cancel out as it tilts laterally, so that the correction remains proportional to the course variation and avoids yaw. Existing systems use gears, heavy and expensive to manufacture, or plastic rods and joints, lighter but more fragile.

After a great number of experiments, trials, errors, tests and finally, in desperation, a call to my Magick-Byrd, Eureka! A ¼” stainless steel rod bent in this way: first, two 90° elbows at its aft end form a crank that transforms the vertical movement of the rod to rotary, then in a horizontal “Z” passing through a slot in the stock of the servo-pendulum blade.

Gear #3 offers a double integration: part of it is hidden inside the lazarette and it is connected internally to the boat’s steering system; it also integrates both steering modes, wind and electric: when the wind is absent or unstable, the vane is replaced with a small tiller pilot inside the lazarette, connected to the forward end of the rod through the coaxial control rod. The paddle still provides the power to move the rudder so the smallest autopilot can steer any size boat with only a few milliamps of power.

The yard in Brittany built small aluminium dinghies for sailing schools and I was able to build a prototype out of aluminium tubes. After a few tests and corrections, gear #3 worked to my satisfaction. But aluminium would not be strong enough to survive in the Roaring Forties, so I had it reproduced in stainless steel in a nearby shop.

After three years of preparation – two working on the boat and the self-steering gear, one to raise the money to purchase new sails, provisioning and all the equipment required for a 9 month voyage – I was able to leave Saint-Malo September 1, 1980. In my previous career, I had been an actor and worked in film, so I took along 16 mm cameras and a tape recorder to document my voyage (broadcast quality video did not yet exist).

The months before my departure had been so intense that I never found time to test the stainless steel version of the prototype. How relieved was I when I saw that as soon as there was enough wind to carry sail, #3 steered as if Jean-du-Sud had been on rails, even under spinnaker!

My plan was to link Saint-Malo, in Brittany, to Gaspé, in Québec, but the other way around the world. I sailed down the Atlantic, rounded Cape of Good Hope crossed the Indian ocean, rounded Cape Leeuwin, south of Australia, but I was capsized and dismasted in the Southern Pacific.

I knew I could never afford a new mast and did not send it to the bottom, as is usually done in such predicament; I hoisted the two sections on deck and reached the Chatham Islands, 600 miles east of New Zealand. Under jury rig, #3 was still steering! The time needed to repair the mast would have me arrive at Cape Horn during the austral winter, so I pulled Jean-du-Sud ashore and flew back to Montreal to edit the film I had shot during this first leg for broadcast on the French network of Radio-Canada and Antenne 2 in France.

I was back at the Chatham Islands October 23, 1982. After two months to splice the mast and refit, I left in the first days of the austral summer. I crossed the Pacific, rounded Cape Horn, sailed up the Atlantic. May 9, 1983 having covered 28 000 miles, Jean-du-Sud sailed into Gaspé bay wing on wing without a pole on the genoa, a feat deemed impossible to any self-steering gear! In 282 days, I never had to steer by hand. This made me conclude that my third self-steering gear could be offered to fellow sailors.

Before I left, electric autopilots had not yet been invented and the only way to make a boat steer itself had been with a mechanical gear. My plan had been to obtain a patent and sell it so I could keep sailing. But I took two years instead of one to complete the voyage and meanwhile, electric autopilots appeared. Huge disappointment: the nautical equipment makers I contacted told me that there was no longer any market for self-steering gears. I had to find another way to earn a living.

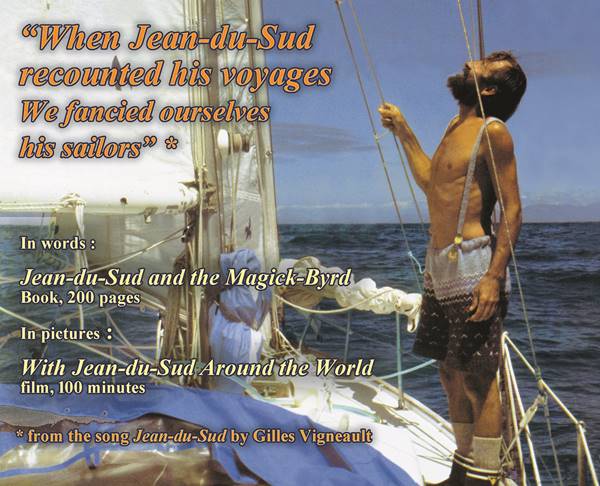

The films I shot were awarded Gold twice at the La Rochelle Sailing Film Festival: part one in 1983, part two in 1985. I spliced them into a 100 min. film, With Jean-du-Sud Around the World. I toured with the film and wrote a book, Jean-du-Sud and the Magick-Byrd.

A few years later, an article in a sailing magazine claimed that autopilots were not dependable, needed a lot of power and after all, there was still a need for self-steering gears. If I wanted gear #3 to keep me sailing, I would have to exploit it myself and in 1989, I created CapeHorn Marine Products to manufacture and market it. To refer to the test I had put it through, I named it CapeHorn.

My professional training had been in the theatre arts and I knew nothing about manufacturing. At first, I sub-contracted the metal and plastic parts and I assembled the gears myself with the tools I had on my boat. I spied at the workshops to learn what tools were needed and how they were used. Any income was reinvested first in tooling, then in marketing. The owner of a machine shop wanted to close it and go sailing; I traded a lathe against a CapeHorn gear. I purchased a welding machine and hired a part-time welder. In 1993, French magazine Voiles et Voiliers published an article describing various self-steering gears and for the first time, CapeHorn was part of the group. The following year, it was Cruising World in USA and Yachting Monthly in UK. Sales increased. I needed help and wondered whether I should hire a welder or a machinist. My nephew Éric was unemployed and said he wanted to work with his hands; I hired him. Through a government program, he learned how to use a lathe and weld.

Gear #3 had been designed for my AL30, a small boat with a transom; I designed a model for larger boats, other models for boats with outboard rudder, scoop stern or boomkin, often combining features of different models to accommodate a given boat. My object is not to take a gear from a shelf and bolt it to a transom – one size fits all – but to offer the most elegant way to make a boat steer itself. Each CapeHorn gear is custom-built for a perfect fit on the boat it steers. To ensure adequate power, yet limit drag, the wetted area of the paddle is proportional to the rudder area of the boat. It does not need spare parts; it is guaranteed for one circumnavigation or 28 000 miles against any damage caused by wind or sea.

Recently, Eric chose to retire. I was sorry to lose this excellent craftsman who produced the CapeHorn gears for the past 30 years. His work had always been impeccable and he did not hesitate to improve quality and finish, even though this meant more work. He also kept the home fires burning when I was sailing in the summer.

One of the first CapeHorn users, Guy Lavoie, replaces him. Guy has circumnavigated with his wife and two pre-teen daughters between 1999 and 2004 aboard Balthazar, a 33′ steel sloop. In 2012, he sailed through the North West passage and in the following seasons, cruised the coasts of Alaska and British Columbia. This recent fall, he sailed Balthazar from Vancouver to the Sea of Cortez.

During his voyages, Guy shot films he presented to various audiences, but Covid put an end to this. He was happy to find a new livelihood. He has built his boat himself and I know he will maintain the quality required to ensure the flawless operation of CapeHorn gears.

I never considered CapeHorn a business but rather a service offered to fellow sailors. Looking back, I see that gear #3 has kept its promises: it steered me around the world, then provided both Eric and myself with a comfortable enough living while allowing me to sail away every summer. I am now 85 years old and I gradually delegate the management of CapeHorn to Guy. However, for as long as I can, I will continue to offer fellow sailors my experience of 60 years in the art of making a boat steer itself.

Age has also forced me to part with Jean-du-Sud, after 50 years sailing together. I entrusted it to a person who promised to take it back to sea. I am gradually detaching myself from my two passions, CapeHorn and Jean-du-Sud.

More than 2 000 boats are steered by CapeHorn. My film has become a classic. In December 2016, the British website ybw.com listed the ten best boat-themed films released in the 1980s, most of them 35 mm theatrical films. With Jean-du-Sud Around the World was among them with this comment: “Many consider this the greatest sailing film of all time. A must see for all sailors”. It can be downloaded through The Sailing Channel., Vimeo or Sailflix. A DVD can be ordered through the CapeHorn website.

The book was published in Québec, then in France. Both editions sold out. It has been translated in English: Jean-du-Sud and the Magick-Byrd. I still have copies. A .pdf version can be downloaded for free. Also a podcast read by myself.

Aafter 60 years, I look back: this voyage, the film, the book, also the gear that steered my boat were my contribution to the art of blue water sailing.

Yves Gélinas